The Goat

Must Be Fed

Why Digital Tools Are Missing in

Most Newsrooms

By Mark Stencel, Bill Adair and Prashanth Kamalakanthan

of the Duke Reporters' Lab, May 2014

By Mark Stencel, Bill Adair and Prashanth Kamalakanthan

of the Duke Reporters' Lab, May 2014

With “traffic and weather on the eights,” 144 times a day, WTOP-FM is one of the most successful and best-staffed commercial news radio stations in the United States. It is “on-air, online, mobile,” as an announcer intones hourly. When it comes to the latest shooting, Beltway tie-ups or other this-just-in news, WTOP.com regularly beats the Washington Post’s website and its TV and radio rivals.

But what about digital tools -- the kind that make it easy for journalists to mine and present government information, sift and analyze social media, crunch massive amounts of data, generate maps and charts, and share reams of source documents? The technologies that have helped distinguish digital journalism from print and broadcast play little role in the big news station’s reporting -- on any platform.

There are countless ways for news organizations such as WTOP and its successful offshoot, Federal News Radio, to tap into data to provide valuable programming for listeners and users, especially in Washington’s lucrative government market. The stations could find stories in government contracts or salaries, or reporters could use (and make available online) census or economic information that would add depth to their coverage of the D.C. area’s traffic woes, transportation issues and sprawling development.

“That’s the kind of work I wish we could do,” said Jim Farley, who led WTOP’s editorial operations for 17 years before his recent retirement. But Farley said it was simply too difficult “to take reporters off the assembly line.”

“We're live and local, 24/7, 365... The goat must be fed.”

- Jim Farley, WTOP-FM in Washington, D.C.

Indeed, off-the-shelf tools now exist that make it simple and cheap for news organizations of any size to develop these kinds of data-driven utilities -- both to inform their reporting and to tell better stories to their audience. WTOP has invested in creating online traffic services for its digital offerings. But with the proliferation of traffic apps such as Waze, purchased last year by Google, “traffic and weather on the eights” will soon face more serious competition.

Meanwhile, WTOP has done little else to take advantage of the revolution in data journalism and digital tools. Like so many local media organizations, its staff devotes the vast majority of its energy to the routine of news.

“We’re live and local, 24/7, 365,” Farley said. “The goat must be fed.”

We started this report to assess the use of digital tools and provide a road map for the work of the Reporters’ Lab at Duke University’s DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy. Along the way, we discovered that despite all the hype we’ve heard in the past five or 10 years, there is still a wide gap between digital haves and have-nots in the use of data reporting and digital tools -- particularly between bigger national organizations, which have been most willing to try them, and smaller local ones, which haven’t.

This report is based on interviews with more than 20 senior editors, news directors and digital editors at newspapers, TV stations and radio outlets across the United States. It also is informed by the authors’ experience working directly on digital journalism initiatives with dozens of local news organizations. We recognize that this is still a relatively small sample and that the subjects were not randomly selected. But we believe our findings represent an accurate picture of the digital age for a wide range of media organizations -- particularly those with small- to medium-size news staffs. Our goal with this report is to start a discussion among the leaders of those newsrooms and suggest ways to expand the adoption of digital journalism.

There’s no question that some news organizations are doing wonderful, innovative data work that has created extraordinary journalism. They have mined large data sets, invented tools and used new reporting techniques to expose corruption and explain complex issues in ways that weren’t possible before the digital age. They’ve been aided by millions of dollars from foundations that have funded innovation through grants, pilot projects, training and journalism education. And yet, hundreds of news organizations are still stuck in the analog past, doing meat-and-potatoes reporting that doesn’t take advantage of the new tools.

In our conversations preparing this report, we’ve often referred to the disparity as if it were the gap in personal wealth, calling the digitally savvy news organizations “the 1 percent” and calling the lagging media organizations “the 99 percent.” We don’t believe the actual disparity is that great, but it probably isn’t too far off, given the realities of newsroom staffing. In the United States and Canada, there are more than 10,000 daily, community and specialty newspapers.

Much of the hype about digital tools and data journalism comes from the largest news organizations. But the vast majority of newspapers, TV stations and radio outlets are small.

Big metro papers get the most attention, but U.S dailies with circulations of 10,000 or less account for more than half of the nation’s papers.

| Circ | # of Dailies | Avg Staff Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| >500k | 7 | 538.6 | |

| 250k-500k | 10 | 208.1 | |

| 100k-250k | 35 | 117.8 | |

| 50k-100k | 44 | 53.4 | |

| 25k-50k | 98 | 31.5 | |

| 10k-25k | 281 | 17.0 | |

| 5k-10k | 296 | 8.2 | |

| <5k | 212 | 5.5 |

Small-market TV newsrooms have smaller staffs, too. In some markets, TV news staffs may actually be larger than their print counterparts, but production processes leave little time to tinker with digital tools.

| Market Rank | Median Total Staff |

|---|---|

| 1 to 25 | 76 |

| 26 to 50 | 57.1 |

| 51 to 100 | 43.3 |

| 101 to 150 | 31.2 |

| 151+ | 22.7 |

Radio news operations are numerous, but staff sizes are almost universally tiny, especially when it comes to full-time employees.

| Market Size | Median Total Staff | Median Full Time |

|---|---|---|

| Major | 7 | 2 |

| Large | 2 | 1 |

| Medium | 3 | 1 |

| Small | 2 | 1 |

| All | 2.5 | 1 |

Sources: American Society of News Editors 2013 Newsroom Census and the Radio Television Digital News Association/Hofstra University 2013 Survey

The U.S. also has 717 local TV newsrooms and thousands more radio news and digital-only operations. Most of these are local news organizations that have correspondingly small staffs. Half the print dailies in the United States have circulations below 10,000, and the average head count in those newsrooms is less than eight people, according to the American Society of News Editors’ annual census. Data from the Radio Television Digital News Association describes similar constraints. In radio, the median news staff is 2.5 including part-timers; the median full-time staff is 1. Television’s production requirements mean local TV newsrooms in smaller markets are bigger than their radio counterparts, but they also have little spare capacity.

Our biggest finding is that the reality of data journalism is out of whack with the hype -- and we need to acknowledge that we’ve been part of the problem. Two of the authors of this report have attended many conferences -- and even spoken at a few -- where we’ve celebrated the successes of digital innovation. The reality, though, is that much of the U.S. media hasn’t shared in the success.

Our goal with this report is not to criticize news organizations that have lagged behind but to explore the reasons for the digital gap, to examine some data tools that have succeeded and to make suggestions on how we can expand the benefits of the digital age to the have-nots. But first, some definitions.

This report is focused on digital tools and, to a lesser extent, on the data reporting those tools are used for. Digital tools include technology that can gather, parse and organize messy datasets (for example, scrapers that collect content from a government website or that convert PDFs to usable text or spreadsheets), as well as publishing systems for making maps, representing complex information in visually appealing ways, creating timelines and sharing original source documents. Sensor technology is another source of data that some inventive journalists are beginning to use to report their stories.

You can find lists, guides and case studies on a number of journalism websites, including DataDrivenJournalism.net, Source and the Poynter Institute’s Digital Tools Catalog, among others. But if you’re in a typical American newsroom, you’ll probably have little familiarity with these tools and practices for the reasons we explain in this report.

Data journalism, which is more widely known, can include anything from small projects based on campaign finance reports and census data to mega-projects analyzing environmental records and local crime data. In the past year, there’s been some encouraging growth in data journalism with new sites such as Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight and enterprising work by journalists such as the Atlantic’s Alexis C. Madrigal. Attendance has jumped at data reporting workshops and seminars hosted by the Online News Association and the Investigative Reporters and Editors’ National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting. Roughly 1,000 journalists attended NICAR’s 2014 gathering in Baltimore -- three times the number of people who attended five years earlier, according to David E. Kaplan of the Global Investigative Journalism Network.

But while that growth is encouraging, the boom in digital journalism is still occurring disproportionately at the larger news organizations, with small papers and many broadcast outlets left far behind. Commercial radio and local TV news are largely absent, which is significant since television is still the way most Americans get their news.

From the point of view of Alberto Ibargüen, president and CEO of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation -- one of the news industry’s primary funders for digital tools and training -- “the biggest failure we’ve had has been precisely at the point of adoption.”

For Ibargüen, the frustrating obstacles are at odds with his experience at well-attended digital news gatherings, such as the one his organization co-hosts each June with MIT’s Center for Civic Media. “You cannot walk away without a sense of excitement or hope,” Ibargüen said. “But fundamentally it is difficult to get traditional newsrooms to adapt” to the changes required of them. “It’s the tyranny of the habit or the process.” Ibargüen also said the industry continues to be dominated by a generation of journalists who came up through a “hierarchal structure” that is “not necessary the best for producing stuff that is of the Web.”

Why do so many newsroom leaders have such a difficult time figuring out how to open these digital toolboxes when peers at other news organizations have shown what even one data-savvy journalist on staff can accomplish?

The most common explanation was the one we heard from WTOP’s Farley: Legacy news organizations remain focused on legacy news. With limited resources, the first goal is to fill airtime or newsprint or stock the website. The goat must be fed, and the easiest feed is the diet it’s been fed for years.

In interviews for this report, we also heard a variety of other explanations for the digital gap: familiar laments about people, budgets and time. Journalists with the know-how are hard to find, and competition for their talents is fierce. Training for existing staff is time-consuming and expensive, especially in an era of constraint, if not deep cuts. And shrinking newsrooms mean fewer people to do the work, let alone take on new forms of storytelling.

But our conversations with news leaders also revealed deeper issues -- part culture and part infrastructure. These are barriers of priority and organization that in many cases journalism executives can address.

Prioritization barriers:

Organizational barriers:

We heard about versions of these barriers from many of the news executives and editors we spoke to -- including some in newsrooms where we assumed priorities and systems would be better aligned with the needs and interests of digital news users.

If there’s someone on the cutting edge of online media who would be expected to take advantage of digital tools and data, you would think it would be Scott Brodbeck, creator of the successful ARLnow.com and two other local news websites in the suburbs of Washington, D.C.

Brodbeck, a 30-year-old entrepreneur who previously worked in local TV, launched the sites because he saw a niche where he could make money in hyperlocal news. But he thinks data journalism adds little value to his business model.

“I just don’t see how it connects with readers,” Brodbeck said. He believes it’s far more valuable to practice old-school journalism by sending a reporter to a county board meeting than to try to mine data from a government website. Brodbeck says digital tools may have value at the national or regional level, where they can mine large databases, but they aren’t valuable for a tiny operation like his. By using smart young journalists, “we are doing reporting that really connects with people,” he added.

How could data help ARLnow? Well, the site could map its rat-a-tat crime coverage together with information from Arlington County’s weekly email compilation of police reports. A tool like this would show crime reports in relation to where Brodbeck’s readers live, work, walk and shop. It might even reveal newsworthy patterns.

But few local news organizations are offering easily built, news-based applications like these. Generally, we found the digital divide is a function of size. The largest news organizations typically have the resources to try new tools and to dedicate staffers to data journalism. There are exceptions, but we found that small news organizations usually were the most focused on traditional newsgathering and lagged behind in digital adoption.

Along those lines, the most common explanation we heard for the lack of interest in digital tools was limited resources. Ned Seaton, editor-in-chief of the Mercury, a 10,000-circulation daily in Manhattan, Kan., says his paper has to cover the news first. “Somebody has always got to do the story in advance of the city council meeting. And somebody has to pick up the police reports,” he said.

Another big problem is lack of awareness of what can be done with data: Seaton’s reporters are fresh out of college and are just learning how government works and how to cover a beat, so they have little familiarity with how tools such as Web scrapers might help them.

“It starts with the fact that we have pretty young reporters,” he said. “There are some pluses to that. They walk in with a knowledge of how to use laptops, recorders. The issue is awareness of what kinds of stories can be done -- even what is public record and what isn’t.”

Still, he teaches reporters how to use spreadsheets and has published a searchable database for property code violations on the Mercury’s website.

Nancy Wykle, metro editor at the Herald-Sun in Durham, N.C., says local news organizations have to focus on the nuts and bolts.

“The challenge,” she said, “is reporters have multiple things they have to cover. The staffing is such that we wouldn’t be able to have a digital reporter. Somebody might be looking at voting breakdowns, and he’ll also be covering county government and local government.”

In order for digital tools to become a higher priority in her newsroom, Margaret Freivogel, editor of the St. Louis Beacon, a local news website that merged with St. Louis Public Radio in late 2013, said the technology needs to become a consistent part of her reporters’ work -- not just a device that is rolled out for special projects.

“I can take on a project, learn what I need to learn and put it together, launch it and it’ll be great,” Freivogel said. “But then if I’m pulled away doing other things for weeks or months or whatever, it sort of fades away.”

Many newsrooms just don’t have the bandwidth to even imagine where to start. At the Hendersonville Lightning in North Carolina, Bill Moss does it all. In the few days before we spoke with him, he wrote everything from an editorial on tax incentives to an interview with the local prosecutor to a cop story. He’s proud that his paper has won the state press association’s award for best website for a small weekly. But he said he simply can’t take much advantage of digital tools.

“I don’t even know what web scraping is. So you can start there,” he said.

That doesn’t mean Moss doesn’t do data reporting -- but it’s primitive. “I do all kinds of investigation all the time, more than the daily paper here, and I even do more campaign finance than anyone else around here,” he said. But it’s done the old-fashioned way. He gets paper reports.

“It’s rudimentary. It’s 1970s-level. I’ve got one paginator/designer/office manager. I say, ‘Here’s the campaign finance reports. Type all these up and we’ll put them in a spreadsheet.’”

For news teams like these, the challenge of deploying digital tools is rudimentary, as well. With small staffs and no shortage of stories to cover, the daily task of keeping track of events takes priority. Digital tools could make some of that work easier -- by, say, providing an automated feed of routine government information that could then be posted online or in print (in some cases, no redundant “newsified” summary required). The tools might even help turn daily stories into bigger stories. (Is there a pattern to that string of car break-ins? Or a trend in those recent home sales?)

But for the top editors and staff in many newsrooms, even those small steps can seem like giant leaps.

For journalists of a certain age, the emergence of digital tools is as much of a cultural revolution as the explosion of newspaper graphics that began in the newly colorized print editions of the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, generating news graphics was obligatory -- an adornment required by news executives and consultants -- but it wasn’t yet a central part of the newsroom’s routine.

We heard echoes of those attitudes and arguments in our conversations with journalism leaders about the use of digital tools today. For some, these tools are ways of supplementing digital versions of stories -- bonus material that is not critical.

A Poynter Institute survey of news professionals and journalism educators found similar evidence. Asked about core news skills, educators ranked the ability to “analyze and synthesize large amounts of data” and “interpret statistical data and graphics” far higher than the professionals did. (Students, who were also part of the survey, fell between the two groups.)

Figuring out how to use digital tools to tell daily stories and cover beats is a “steeper learning curve” for journalists and their bosses, said Melanie Sill, a former senior newspaper editor who now is executive editor of KPCC/Southern California Public Radio in Pasadena. Using data and visualization tools requires “thinking about how you find stories and how you look at information in different ways,” Sill said.

One example from her newsroom is KPCC’s “Fire Tracker” -- a standing feature that updates automatically three times a day with new information from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s website. It shows that a little ingenuity can produce a digital feature that provides valuable journalism at little ongoing cost. Still, there are hurdles to creating a tool like that.

“For all newsrooms, using data is not like learning to post to WordPress,” Sill said, referring to the widely used web publishing platform. “It’s not just another set of mechanics to use…. It’s not an easy kind of plug-in.”

On top of that, journalism is a profession generally known for attracting people who are better with words than data. “We’re kind of innumerate,” Sill said.

Another broadcast newsroom that has invested time and brainpower into using digital tools is WRAL-TV, an independently owned CBS affiliate in North Carolina’s Raleigh-Durham area. Like the area’s largest local newspaper, the News & Observer, WRAL was among the first local news organizations to devote resources to its Web presence in the mid-1990s -- in part because of the area’s high concentration of universities and technology businesses. But even at WRAL, digital tools have primarily been associated with the station’s project work.

“One of our challenges at WRAL,” said Kelly Hinchcliffe, special projects producer, “is to incorporate these data journalism tools into our everyday coverage. We are trying to encourage and teach more reporters to use the tools, such as Excel and DocumentCloud. My job includes a lot of work on special projects, including long-term investigative stories, so I have time to get familiar with new tools, test them out and incorporate them into my reporting. But this is not always possible for reporters and Web staff who have to fill newscasts and update the website every day.”

Newsrooms often lack the people and systems to make that happen.

“When you see data visualization done really well, it’s just stunning,” said Freivogel of the St. Louis Beacon. “But to do things that well, you need an unusual combination of skills: partly visual, partly journalistic, partly computer.”

Freivogel echoed many of the experiences we have observed and heard about in our interviews:

The deck is stacked against these newsrooms in multiple ways. They don’t have control, they don’t have the know-how and they don’t have the publishing systems they need to make full use of the tools that are available to them.

“If you’re going to be more and more digital, why can’t you take advantage of the technology to tell stories better?” asked Marty Kaiser, editor and senior vice president of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Kaiser used a vacancy to create a developer position in his newsroom and hopes to add more. He also is breaking down barriers between his staff and a separately managed IT staff. “You need the ideas of reporters to mesh with the ideas of developers,” he explained.

But Kaiser said those efforts can be challenging because each team speaks different languages and sometimes has different priorities and imperatives. Some journalism-technology conversations, he said, can be like a typical consumer trying to keep up while he asks a salesperson about the specs for a new gizmo: “It’s like I’m going to BestBuy.”

"If you’re going to be more and more digital, why can’t you take advantage of the technology to tell stories better?”

- Marty Kaiser, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

How can editors and news execs cut through the organizational and cultural barriers? One answer: small, interdisciplinary news teams that include members with a range of digital and editorial skills. Cobbled together for their complementary abilities, like the characters in The Avengers or The Magnificent Seven, these teams of specialists have been successful in places where top editors had the willpower to create them.

One of these data squads is the News Applications (or “News Apps”) team at the Chicago Tribune, now headed by Ryan Mark, the Trib’s director of digital product strategy and development. But even at a paper with the Tribune’s resources, Mark said the team needed leadership buy-in to stay focused on stories the team thought would have the biggest impact with digital readers. The newspaper was wise to “bring in a bunch of folks who’ve been working on the web and living on the web,” Mark said. He also said his bosses gave the News Apps team the freedom and standing they needed to reject ideas they thought wouldn’t click with users. Over time, that helped increase digital literacy and ideas across the newsroom. “The folks we have worked with the most really get it,” Mark said.

Of course, few newsrooms have the horsepower to create the kinds of original Web applications that the Tribune and other big papers have, even after the cutbacks of the past decade. But some entrepreneurial newsrooms in smaller markets have also done exceptional work.

As editor at the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Nancy Barnes made data reporting and digital tools a priority. She read up on data visualization and visited newsrooms that were leaders in the field. Even when she had to cut jobs, Barnes was still able to use a handful of “nonessential” vacancies to begin building a data dream team in her newsroom.

The process was challenging and took time. In fact, it never ended. When Barnes left Minneapolis in 2013, the Star Tribune was still short-handed on the design and development expertise she wanted. And as she took command at the Houston Chronicle late last year, Barnes said hiring more digital and data know-how will now be a priority in her new newsroom, too.

“Newsrooms need to be constantly recreating themselves,” she said. “Every year the world changes.”

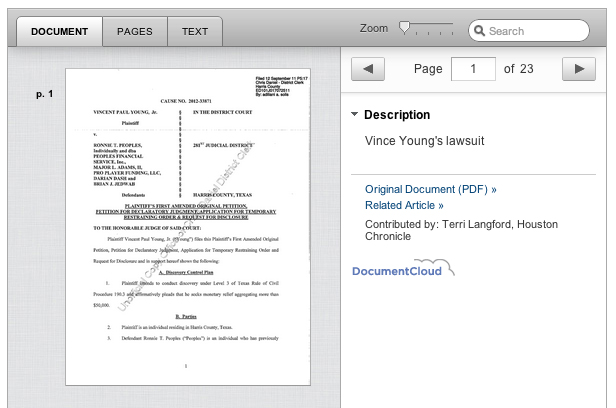

You don’t have to be as big as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel or the Minneapolis Star Tribune -- and you don’t need much money, if any, to use digital tools to broaden your offerings for readers, viewers and listeners. There are plenty of free and low-cost web applications that are available for everything from posting PDFs to creating cool charts. This includes web services as widely used as Google’s Media Tools and the Tableau data visualization tool. It also includes services built specifically for newsrooms, such as DocumentCloud.

DocumentCloud was created in 2009 by a partnership of ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative news organization, and the New York Times, with support from a Knight Foundation grant. The web-based service, now run by IRE, allows journalists to post and share the primary source documents they use in their reporting. It also allows organizations to annotate those documents and enlist help from other news organizations as well as the public.

On one recent day, the dozens of documents posted included a 23-page federal inspector general’s report on day care health and safety licensing requirements shared by the nonprofit news site the Connecticut Mirror and a pair of letters between the Energy Department and the state of Washington over the Hanford environmental cleanup site shared by Seattle-area TV news station KING 5. Of the more than 500 journalistic organizations listed as users of the service, we found that most (60 percent) were local news services.

DocumentCloud, like Google and Tableau, has been a great success because it meets a need of many journalists, it’s free and it’s relatively easy to use. Newsrooms just open an account and start uploading documents -- no coding skills required.

But using these tools still requires that someone dedicate time to mastering them -- and advocacy if more than one journalist is going to understand what each tool can do.

During his first year as managing editor and director of content at DeseretNews.com and its parent, Deseret Digital Media in Salt Lake City, Burke Olsen said he wanted to make sure his new team had time to systematically “experiment” with third-party web tools. He assigned members of his staff specific applications -- such as the online infographic generator infogr.am and a timeline tool developed by Northwestern University’s Knight Lab, among others. After a month of tinkering, the employee would report back to the team on how the assigned tool could help with their storytelling.

Using inexpensive and freely available “plug and play” tools frees Deseret’s staff developers to focus on the company’s longer-term priorities without holding back his editorial team’s ability to do different kinds of journalism. “The end goal is to create a better experience,” Olsen said.

News organizations often think they are making a smart trade-off when they focus on covering news of the moment instead of using digital tools more creatively in their coverage. News gets the page views, the thinking goes, so it’s better to have a reporter churn out several blog posts a day rather than focus on a longer-term data project.

But this focus on the fleeting comes at a cost, too. In addition to the staffing required to generate a steady flow of frequently updated news reports, it ignores the fact that content produced with digital tools can have a longer shelf life. Some of these packages are updated automatically and generate ongoing traffic over time.

Reporting on crime, for instance, is a daily staple in most local and regional newsrooms. So is basic government coverage -- from zoning decisions to the salaries of state and local officials. This day-in, day-out work can become a more powerful ongoing story when told using tools that link and present the underlying reporting in ways that add meaning and context.

Since its launch in November 2009, the Texas Tribune has made data-driven, interactive journalism a core offering -- to the point that “Data” is a sitewide top navigational link. From a multifaceted look at statewide school performance and spending information to a searchable guide to the financial interests of state and local officials (the “Ethics Explorer”), the nonprofit news service actively maintains numerous databases, sometimes working with other Texas news partners. And the Tribune’s staff has said these offerings drive a considerable portion of the site’s traffic (as much as two-thirds, then-reporter and applications developer Matt Stiles estimated in a 2011 Poynter.org interview).

“We believe in the power of data,” Evan Smith, Texas Tribune’s editor-in-chief and CEO, once wrote in response to complaints about its first public salary database. “We believe in the value of creating more thoughtful, engaged, and informed citizens by giving them the tools to be those things and more (we believe in teaching a man to fish rather than giving him a fish).”

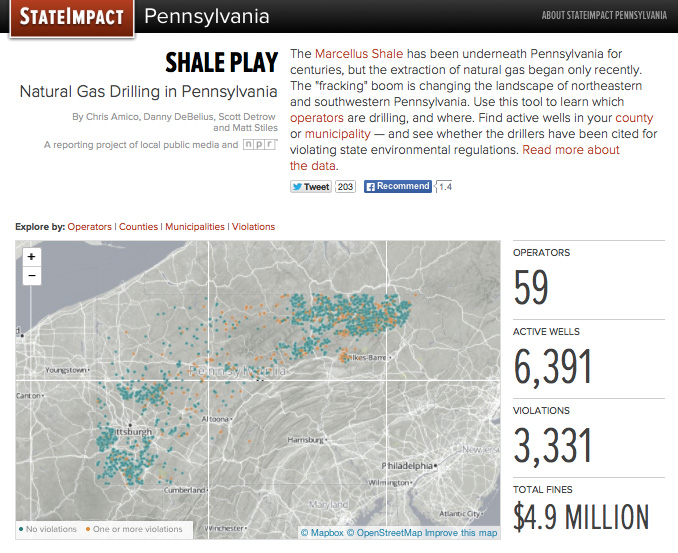

Other news organizations have started to believe in the “power of data,” too. One example is StateImpact Pennsylvania, an on-air and online partnership between public radio stations WITF in Harrisburg and WHYY in Philadelphia that focused on the effects of the state’s “fracking” boom. The site offers an updated interactive map that displays active wells and drilling violations that was originally developed in collaboration with NPR data journalists in Washington. In addition to supporting the interactive, the underlying data in the app also generated ideas for traditional news stories.

Tim Lambert, WITF’s multimedia news director, said creating and maintaining a database has been no easy task, even with help from the data journalists at their national news partner. “It does cost money. It does take time. It does take effort.” But Lambert also said the app has been worth the price. Even two years after the web app’s debut, “Shale Play continues to be one of the most visited pages on our site,” he said.

The shale app “is a great lesson in the long tail,” added Chris Satullo, WHYY’s vice president of news and civic dialogue. In fact, Satullo and Lambert have already joined forces to apply those lessons again -- this time by partnering with several other public radio stations to focus on urban issues across Pennsylvania. “A great deal of that will be data-driven work, too,” Satullo said.

The Amarillo Globe-News is another news organization that has discovered how much interest interactive data presentations can generate. One of its most successful databases tracks registered sex offenders -- complete with maps and mug shots -- using information from the Texas Department of Public Safety.

The Globe-News’ core digital team -- made up of both traditional journalists and specialists in social media and blogging -- produces multiple databases and other tools to cover various local beats. That includes regularly reporting on teacher and government salaries and city food inspection reports. It’s an impressive array for a newspaper of its size (circulation: about 60,000 daily, plus another 10,000 or so on Sundays).

“Our barriers are the same ones I suspect you’d find at any newsroom -- number of people to do the work, the daily grind and training,” said Ricky Treon, who was the paper’s online editor. “I think these are hurdles that get overcome by retaining quality journalists so that newsrooms aren’t in a constant state of teaching reporters/editors how to use these tools.”

Making this kind of work possible requires more than newsroom know-how. It takes management willpower -- the kind that can only comes from senior news leaders who are willing to make effective digital journalism a top priority. That’s no easy task in a time of financial constraint and shrinking staffs.

Kaiser, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s editor, said the trade-offs are worth it. But he also was clear: The trade-offs are real. “There’s a lot of stuff we just don’t cover as before,” he said. But being relevant digitally means doing more than “just reporting the news daily.”

“We have to be really careful picking our spots -- what we’re going to do and not going to do,” Kaiser said.

Kaiser also noted that prioritizing impact journalism -- like the paper’s recent series documenting delays in medical screenings for newborns across the country -- can also help in a time of constraint. The work resonates with the audience. And the reaction and recognition it generates locally and nationally can boost newsroom morale. “The whole idea is to have as much impact as possible,” he said. “If you’re doing great work and can get national recognition sitting here in Milwaukee, that’s great.”

The trade-offs can be even trickier in broadcast newsrooms, most of which have far smaller newsrooms than their print counterparts, even in some of the largest markets in the country.

Jim Schachter, vice president for news at New York’s WNYC, moved to public radio from the New York Times, where he was a senior editor. So he has some idea what it takes to stand out in a competitive media market -- nationally as well as locally. And for him, enterprise reporting powered by data journalism and digital tools is one of those things. Data, he said, is “central to our identity as a 21st century news organization. This is something you should do well.”

At WNYC, the power of that kind of work became clear shortly before his arrival, with a 2011 story on the city’s stop-and-frisk policy done by reporter Ailsa Chang with help from data journalist John Keefe. The reporting spotlighted New York’s high rate of marijuana arrests, especially in poor neighborhoods, and possible connections to illegal searches. Online versions of the work used digital tools to provide an interactive map that reinforced the stories’ findings.

For Schachter, this is the kind of work that can help a news organization stand out. “My editorial focus is on, to the maximum extent we can with the number of people we have, [doing] big important stories that make a difference in people’s lives,” he said. “And one of the ways of doing high-impact enterprise journalism is to do investigative reporting. And some of the best investigative reporting is driven by deep engagement with data and statistics.”

Part of making that formula work is focusing on “projects that are aligned with what you understand to be important.” But it also requires the kind of high-level buy-in Schachter said he has from his bosses, all the way up to the station’s CEO. Data journalism, he said, is part of WNYC’s plans “to remain relevant and cool and a leader.” It is “a major part of this organization’s digital growth strategy…. It’s something we decided was really important.”

And on top of that, data journalism is something his staff can do to distinguish its work in a market filled with print, TV and digital competitors all angling for their own ways to capture the attention of their audiences.

“We’re not ever going to have a helicopter,” Schachter says, “but we have this.”

We began this report with the tale of WTOP in Washington and its need to fill air time 24/7. That need is very real, not just for 24-hour news radio but for any news organization.

We believe, however, that the success stories of organizations in news markets as diverse as New York (WNYC) and Amarillo (the Globe-News) show how digital tools and data reporting can produce valuable journalism -- in print, on-air and online.

Getting the full value of that work requires that news leaders understand the potential and what it takes to realize it. It also requires that newsroom executives coordinate with their business counterparts to make sure the work gets the marketing, promotion and sponsorship it deserves, given its power to engage news consumers.

That’s a conversation that doesn’t always come naturally in organizations that have church-and-state walls between journalists and the business types. But it’s a conversation that many of the people who have done pioneering work in data journalism know needs to happen if the audience and stories their work generates are going to help the industry’s bottom line.

A few tools that newsrooms of almost any size can use:

NPR Visuals editor Brian Boyer, who also was the first editor of the Chicago Tribune’s News Apps team, said sponsorship is key to sustaining the kind of work he and his journalists do. And he is certain the solution does not involve designing around today’s most commonly used online advertising units. “Sponsorship should be more interesting than a cube, but our teams aren’t great at selling it,” Boyer said, speaking about the news industry as a whole.

Boyer’s team has been able to coordinate with NPR’s sponsorship and other business units to try to find solutions. But Boyer also noted that the level of direct coordination between an editorial team and a news organization’s other business units “would not be a legal thing in a lot of newsrooms.”

This is territory where senior news executives need to tread.

Within their newsrooms, news leaders also can look for ways to personally sponsor innovation. But that may not be any easier than opening new lines of communication with their company’s business leaders.

“A lot of people are still mad at the Internet for existing.”

- Michael Maness of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Michael Maness, the Knight Foundation’s vice president of journalism and media innovation, sees the gap in “transformational leadership” as a huge obstacle to the kinds of tools and innovation that his organization has been funding. But those tools and practices will have a tough time without leaders who have the “intellectual curiosity” to “embrace new disruptive technology” -- and see it as helpful, “not an enemy.”

“A lot of people are still mad at the Internet for existing,” Maness said.

He also said news leaders need the courage “to stop doing something,” without which there will never be “the time and space and money to try new things.”

Other innovators in the news business see the barriers in much the same way. KPCC’s Sill said much of the industry lacks the flexibility it needs to integrate new practices, such as data journalism. That’s “not the inherent culture of mainstream newsrooms,” she told us. “Dealing with change is hard for any incumbent organization…. Most of them don’t have training embedded in the culture -- training and learning.”

That cultural shift is harder to make happen when you don’t think you have the “structure to fulfill your basic function every day,” she added -- a circle of constraint that can keep newsrooms focused on what they have always done instead of what they need to do differently.

Breaking that circle and taking advantage of digital tools to better serve our audiences requires that all of us in news leadership take the questions that dominate our days -- people, budgets and time -- and ask them in new ways:

How can we innovate more within the reality of our current constraints? What does our audience really want and expect from us? Those questions can sound pretty abstract, but reducing them to specific, practical terms can make the big challenges less daunting.

Personnel questions: Who on our staff understands how to tell stories digitally, regardless of where they work now? Would shifting them (temporarily, some of the time, all of the time) create professional development opportunities -- both for them and for staffers who would fill in?

Coverage/audience questions: How much of an audience is there for all of our routine coverage anyway? Which stories can we stop doing so we can tell high-impact stories that are data-driven, visual and interactive instead? Are there topics or beats (traffic, schools, real estate, economic development, crime) where digital tools will have the most impact on our audience and our community? What stories will we find by wading into the data? How can our audience help?

Tool and process questions: Which low-cost and open-source tools can we use to do this work? Can we create digital “sandboxes” that allow our news staff to work around the constraints of existing publishing systems? Who else can partner with us (other news organizations or academic journalism programs)? Where can we find free or inexpensive training?

Organizational questions: Can we use editorial experiments to make a case for the newsroom’s technology needs? Or even our staffing needs? How can we make sure that any new know-how is retained and shared as broadly as possible with others in the newsroom? How can we present and promote our innovations to excite our audience -- and our sponsors?

As leaders, questions like these can help us end a decade of aimlessly saying “no” to our highest editorial aspirations and better harness the power of digital innovation in small and powerful ways.

We recognize that the goat must be fed, but we think it’s time for editors and news directors to show more imagination about what it can eat.

This report, also available in a PDF version, is a product of the Duke Reporters’ Lab at the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy in the Sanford School of Public Policy. We welcome your feedback on the Reporters' Lab website or via Twitter: @reporterslab.

The report was written by Mark Stencel, Bill Adair and Prashanth Kamalakanthan. The report website was developed by Aaron Krolik using the Foundation 5 framework.

Our findings are based on interviews with people in more than 20 U.S. newsrooms and journalism organizations, as well as the authors’ personal experience working directly with local media partners.

The conclusions -- as well as any errors -- are entirely our own. But we are grateful for the insights and examples we heard from the following colleagues: Nancy Barnes of the Houston Chronicle; Brian Boyer of NPR; Scott Brodbeck of ARLnow.com; John Davidow of WBUR-FM in Boston; Jim Farley of WTOP-FM in Washington, D.C.; Margaret Wolf Freivogel of the St. Louis Beacon; Anders Gyllenhaal of McClatchy Co.; Kelly Hinchcliffe of WRAL-TV in Raleigh, N.C.; Alberto Ibargüen of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; Marty Kaiser of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; Tim Lambert of WITF-FM in Harrisburg, Pa.; Michael Maness of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; Ryan Mark of the Chicago Tribune; Bill Moss of the Hendersonville Lightning in North Carolina; Burke Olsen of Deseret Digital Media; Chris Satullo of WHYY-FM in Philadelphia; Jim Schachter of WNYC-FM in New York; Ned Seaton of the Mercury in Manhattan, Kan.; James Eli Shiffer of the Minneapolis Star Tribune; Melanie Sill of KPCC-FM in Pasadena, Calif.; Jennifer Strachan of KPLU-FM in Seattle; Patrick J. Talamantes of McClatchy Co.; Ricky Treon of the Amarillo Globe-News in Texas; Ellen Weiss of E.W. Scripps Co.; and Nancy Wykle of the Herald-Sun in Durham, N.C.

At the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media & Democracy in Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy, we appreciate the support of Director Philip F. Bennett, who is the Eugene C. Patterson Professor of the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy; and Associate Director Shelley L. Stonecipher.

Special thanks also to Lani Harac, managing editor at School Family Media and PTO Today, for her editing.

Mark Stencel is a Digital Fellow at the Poynter Institute and NPR’s former managing editor for digital news. At NPR, he oversaw news coverage for the radio network’s website and other platforms, from mobile gizmos to social media. He previously worked in both print and digital journalism and on the editorial and business sides of publishing, holding senior positions at the Washington Post, Congressional Quarterly and CQ’s Governing magazine. Stencel also was a technology columnist for CQ and Governing (then owned by the Poynter Institute’s Times Publishing Co.). And he covered science and technology for the News & Observer in Raleigh-Durham, N.C.

Stencel began his career at the Washington Post as an assistant to political columnist David S. Broder and he was the co-author of two books on media and politics. He is a board director for the Student Press Law Center and an advisory board member for Mercer University’s Center for Collaborative Journalism in Macon, Ga. Having graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in Soviet studies the year before the Soviet Union ceased to exist, his credentials as a media “futurist” should be considered with journalistic skepticism. (mark[dot]stencel[at]gmail[dot]com | @markstencel)

Bill Adair is the Knight Chair of Computational Journalism at Duke University. The creator of the Pulitzer Prize-winning website PolitiFact, he has been recognized as a leader in new media and accountability journalism. He worked for 24 years as a reporter and editor for the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times) and served as the paper’s Washington bureau chief from 2004 to 2013. He launched PolitiFact in 2007 and built it into the largest fact-checking effort in history, with affiliates in 10 states and Australia.

He has made hundreds of appearances on television and radio on programs such as the Today Show, Nightline, Morning Edition, All Things Considered, Reliable Sources, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal and the Colbert Report. His awards include the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting (with the PolitiFact staff), the Manship Prize for New Media in Democratic Discourse and the Everett Dirksen Award for Distinguished Reporting of Congress. (bill[dot]adair[at]duke[dot]edu | @BillAdairDuke)

Prashanth Kamalakanthan, who graduated from Duke University in May 2014, was a research assistant at the Duke Reporters’ Lab. He has written about race and political economy at The Nation, Asia Times, Alternet, MSNBC and elsewhere. (@pkinbrief).

Aaron Krolik is an electrical engineering student at Duke University and a software engineer at the Duke Reporters’ Lab. He has worked as a research and teaching assistant in Duke’s computer science department, a financial software development intern for Bloomberg LP and a biochemistry research assistant at Duke’s Medical Center. His passions lie in science and technology, journalism, education and music, and he is looking for ways to bring them together. (aaronbkrolik.com | @Aaron_Krolik)